STEPHEN VOLK

The Creatures That Make Us Human16/5/2022 My new, wide-ranging, collection of stories, Lies of Tenderness, was not written with an overarching theme in mind—though it might well have one; they were all written by the same author, after all (and I try to eke out a common thread in my Story Notes)—but the book is said to contain 17 tales that explore “hidden truths and secret wishes, the paths not taken, and the creatures that make us human”.

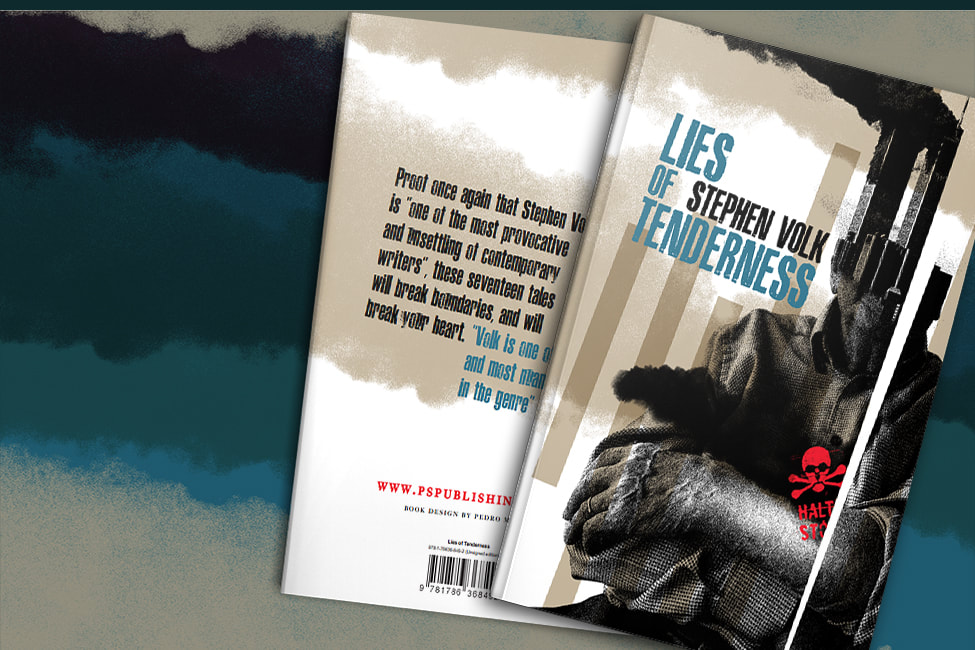

With that last, potent, phrase in mind. I’d like to talk about one story in particular, called “A Meeting at Knossos”. It was the very last to be written, in late 2021, and last to be added to the volume, jettisoning another that didn’t quite fit. I have been fascinated by the Minotaur for as long as I can remember. It’s always struck me as the archetypal monster story and I could never understand why it hadn’t ever, to my knowledge, been exploited in cinema. I first pitched The Minotaur as a film idea to Milton Subotsky (the producer of the classic Amicus horror and fantasy films) way back in the 1970s when I first came to London. I thought you could update the Greek myth, much as Hammer had done with The Gorgon, by setting it in their beloved mitteleuropean world of 19th Century gothic. Subotsky was far from convinced, so that was that. More recently, visual influences rather than literary ones brought it to the front of my mind. I think it’s exceptionally hard to draw or sculpt a human figure with a bull’s head and make it work, let alone have it embody the horror and pity imbued in the legend. The artist Beth Carter succeeds in this brilliantly, and her Sitting Minotaur and Minotaur Reading are direct catalysts for this story, even though I know that such artists as Michael Ayrton and, obviously, Picasso, have been obsessed by the character before. The double idea that Daedalus not only created the labyrinth but fathered Icarus sparked me to put pen to paper. I had no idea where the meeting of the fallen Icarus and the freed Minotaur would lead, but it turned out to be about someone who has the chance of redemption—of change—but the question is, are they capable of making it? I admit, I set out wanting wanted to save the poor creature and rehabilitate the monster. Like Victor Frankenstein’s creation, I thought, he was damaged not so much by an accident of birth but by the way he’d been treated. Some of this was, I’m sure, influenced by my reading of The DevilYou Know by Dr Gwen Adshead and Eileen Home. Adshead is a forensic psychiatrist who has worked on the rehabilitation of violent offenders at Broadmoor hospital. I was struck when she described such patients as having been “witness to a trauma; the trauma which is their own life”. That could be said to be the autobiography of my Minotaur—a retelling that I hope releases the age-old monster to be interpreted in a new way. Even if the outcome of the story didn’t go the way I was expecting . . . Extract from “A Meeting at Knossos” I followed the string, hand over hand, until I emerged from the belly of the earth. The scent of sea lavender and the tang of bergamot tickled my nostrils and made them widen. Blinded, I felt the sun on my fat, flat toes. It tickled the coarse hairs on my shin as I extended my left leg from my prison. They were as little accustomed to the light as I was. “Theseus, my love.” That last word caught like a nut in the throat of a lark, its beautiful song curtailed in a knot of sudden abhorrence. I lowered my hands from my eyes, allowing them in slats to endure the blaze of Helios, my grandfather, in the sky. My bull eyelashes fluttered. A vision as though through water took form. I remembered water, vaguely. Not seen it for an age, other than the cavernous trickle tasting of iron and moss that had been my wine for too many days to count. I took her first to be my mother, but no. Princess Ariadne, my half-sister. A pip when I’d last seen her. Elaborate hair, long dress, breasts exposed. Always the fashion-conscious one. Standing there with the ball of twine in her trembling fingers. Chest rising and falling in horror at the monster she beheld. Hand over hand, I reached her. She would have planted a kiss on the cheek of her lover, I was sure. But her half-brother? No. I was not Theseus. I was something else. The Prince of Athens lay dead at the centre of the labyrinth. He’d come to dispatch me, but I’d dispatched him. His club had snapped in two across my forearm. I remembered feeling his Adam’s apple jiggle against my palm. His neck had grown hot and pulpy. His shiny helmet had fallen off. So much for shiny helmets. He’d crept up on a sleeping creature to murder it. Not very sportsmanlike. I dropped the ball of twine at my feet. I had need of it no longer. “Sister,” I breathed, as if my first breath. The dagger fell from her fingers before I realised she had cut her neck from ear to ear. I backed away so that she didn’t splash me, but it was a bit late for that. I watched her girlish frame crumble and her limbs thrash in a scarlet, widening pool under her. Then, after a while, she was still. I had seen many a dead maid before. It was not new to me. But it was a disappointment. I would have liked to have caught up on old times, after all the years that had passed, but she’d put paid to that, well and truly. I wasn’t sure what to do. There wasn’t much I could do. So I knelt and lapped up the blood before it dried. No sense wasting it. The taste reminded me of the time I nipped my mother’s breast with my teeth and got a slap for it. I could still feel the sting on my cheek. That was long before being confined to the bellowing dark. Back when I was loved, or thought I was. Stepping over my sister, and with no destination in mind, I walked north, avoiding the Royal Road with its traffic and people. Crunched olives underfoot, juniper berries, thorns. Nothing smelled as strong as the fiery rot of the sun. My skin was unused to such attention, and oozed, and shone. Half-cooked and half-exhausted—half most things—I reached the coast and took myself unto the waves, washing away the stuff that stained me. My sister reddened the surf. Poseidon hissed his thanks for the offering by means of the waves combing the sand then retreating. Just as I turned back to face the beach I saw a strange shape adorning the rocks, so jagged I first took its inelegance to be the buffeted sail and mast of a wrecked ship. Yet it also resembled as much an arm stretching to the firmament. What creature, then, was this? I trod carefully closer. White petals fluttered in the air about me. I caught one. Opened my fist. It was a feather. I snorted and let it off into the wind like a butterfly. The thing had vast wings but I could not in all honesty call it a bird. And it had a man’s head and body but I could not in all honesty call it a man. Whatever it was, it was dead, I was sure of that. I leaned closer to see if the meat was fresh. Old habits die hard. I sniffed its pale cheek. Touched the long bones covered in feathers, thinking I might break off a piece. The beast flexed its muscles with a rattling groan. The wing flapped out of my grasp. I fell over backwards, bruising myself, and squatted silently on a rock formation for a while to see if it awakened. I don’t know why I sat there, looking at its shape. Why did it interest me? Perhaps I thought it might metamorphose into a man. Or metamorphose into a bird. Either would have satisfied. Neither happened, so I dragged it to the beach to prevent it being swept away by the tide. Why that mattered to me, I cannot say. Only when I laid it flat did I see the straps and buckles that held the wings to its back. I loosened them and they came away in my hands. Not part of the creature itself but an attachment. Not of bone and flesh at all, but of wooden fronds jointed and planed by human hands. I peeled away the broken wings and tossed them into a feathery pile of cracked beeswax and leather, revealing a man, a youth, blood-soaked from his wounds. I revealed you. “A Meeting at Knossos” is one of 17 stories by Stephen Volk collected in Lies of Tenderness, available now from PS Publishing. www.pspublishing.co.uk

0 Comments

Stephen VolkScreenwriter and author Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed