STEPHEN VOLK

|

A short interview about ghost stories and writing, hosted by Mark Norman of The Folklore Podcast - recorded live at the 2023 UK Ghost Story Festival at the Museum of Making in Derby.

1 Comment

Film (Year) Director:

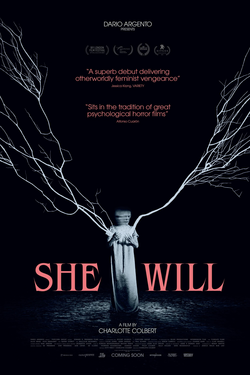

Don't Look Now (1973) dir. Nicolas Roeg The Innocents (1961) dir. Jack Clayton Taxi Driver (1976) dir. Martin Scorsese The Devils (1971) dir. Ken Russell Macbeth (1971) dir. Roman Polanski Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) dir. Peter Weir Apocalypse Now (1979) dir. Francis Ford Coppola Requiem for a Dream (2000) dir. Darren Aronofsky The Night of the Hunter (1955) dir. Charles Laughton Dracula (1958) dir. Terence Fisher Don't Look Now 1973 United Kingdom, Italy This film had a profound and visceral effect on me and has been embedded in my psyche ever since. A masterpiece of every aspect of cinematic art. The Innocents 1961 USA, United Kingdom The most effective and precise rendition of a ghost story in cinema, with an unforgettable central performance. Taxi Driver 1976 USA The first film where I found myself experiencing an abnormal mind from the inside. Rewards endless rewatching. The Devils 1971 USA, United Kingdom A physical onslaught of a film which changed my idea about organised religion, and history, forever. I have never been the same since. The fact the film has not been released in its intended form is a travesty. Macbeth 1971 USA, United Kingdom Polanski achieved at a stroke what my English teachers never had: he made Shakespeare not only intelligible but compelling. Picnic at Hanging Rock 1975 Australia A film that is not just a mystery, but about the nature of mystery and the inability of human beings to accept the inexplicable. Masterful and eternally resonant. Apocalypse Now 1979 USA Far more than a war film or mythic quest, it throws of the shackles off its genre to become a meditation on madness and horror. Unforgettable. Requiem for a Dream 2000 USA Simply unrelenting and unapologetic. Funny, disturbing, extreme, challenging - all I ever want from cinema. The fact that some people find it unbearably grim only makes me love it all the more. The Night of the Hunter 1955 USA This nightmarish horror with children at the centre, full of classic imagery and a blood and thunder perforamance from Mitchum, always had to be on my list. Dracula 1958 United Kingdom There had to be one Hammer here, and it's this. There is no better scene in the history of horror than the climactic confrontation between Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee. Etched into my mind and absolutely treasured. It never gets old and never fails to get the blood pumping. Further remarks: I have chosen these films with two strict criteria: That they had to have had a profound effect on me on first viewing. Secondly, that their lasting legacy had to have stayed with me and imbued my own creative life. All the films on the list have done, some directly and massively influencing my writing, while others have provided constant inspiration by their greatness. Thanks for the opportunity to share them. Close, but no cigar: A Clockwork Orange They Shoot Horses, Don't They? The Devil Rides Out Quatermass and the Pit Some Thoughts on Writing21/2/2023 I was up in London recently to meet Charlotte Colbert, the incredibly talented director of the excellent horror film She Will. On the train home, I ran out of things to read, so I idly wrote down - in vague response to Boris Starling, who'd written something similar online - my CONTENTIOUS ADVICE FROM A CONTRARIAN WRITER. Obviously, your mileage may vary.

But here goes: 1. Arrive on time, every time. No excuses. 2. Nobody will die if they don't get it Monday. 3. If a project is suffering or you are suffering, quit. (I have walked 3 tmes in 35+ years - all for good reason, but all painful decisions.) 4. "No" is a beautiful word. 5. They never give you enough time to get it right, but, miraculously, there is always time to do it again. 6. Shouters have already lost. 7. Take inspiration from other people's writing, but unless you add something of your own life experience, it's worthless. 8. "Resilience" is a dangerous concept - writing skill is nothing to do with strength of character. Be aware that there are those who have trouble setting one foot in front of the other (creatively or psychologically) - and it is not a flaw. Support them, because they might be the smartest person in the room. 9. Don't take every job that is offered. Your career is your choices, and you have to live with that. (Then again, no sin to make a living.) 10. Have self doubt. Those who don't tend to be pricks. 11. Not all criticism is valuable and too much can capsize a perfectly good boat. 12. Bottom line, look after your own soul and the writing will take care of itself. 13. You might be a sceptic and an atheist, but it doesn't mean your characters aren't on a spiritual journey. 14. Lose yourself in your writing - in every sense. 15. An actor's question, and the director's answer, might be about something you never thought of. 16. You don't choose your subjects (or obsessions), they choose you. 17. Don't say you're "lucky" - you are talented and you work hard. 99% of the population would love to do what you do, but that doesn't mean you shoulod be embarrassed or "grateful" for doing it for a living. 18. On those days you might, god forbid, hate what you're doing - for whatever reason - don't resist the pull to the dark or try to talk yourself into believing it's all rosy. Take a deep breath, sink deep, and, god willing, come out the other side with renewed vigour. (In short: fucking wallow.) 19. No job is beneath you, or beyond you. 20. Social media is an addiction, and like all addictions, both loathsome and offering certain irresistable benefits. 21. A director once told me the world is divided into nice people who don't get films made, and absolute shitbags who get movies off the ground. 22. Writing free for "exposure" is toxic and unrelenting. And now they aren't even guilty about asking you to write for no pay. It's a disease. 23. Occasionally write a story for yourself that nobody else will eer read. It's the best way to recalibrate your inner writer. The secrecy of exploring an idea without any commitment to outcome. 24. Remind yourself of the time that script note you resented, and resisted at all costs, turned out to be right. 25. Dickens might not have written for EastEnders if he was living today. He might have become Guillermo Del Toro or Steven Spielberg. 26. People will always ask you questions about that scene the director wrote. 27. Sometimes writing is like beating sheet metal with a sledgehammer. Sometimes the sheet metal is you. 28. If you have spare time on a train journey, don't write a list, write a scene. 5 Questions with Stephen Volk26/1/2023 Stephen Volk is an upcoming guest at the UK Ghost Story Festival in Derby, February 2023. These questions were put to him by festival director Alex Davis.

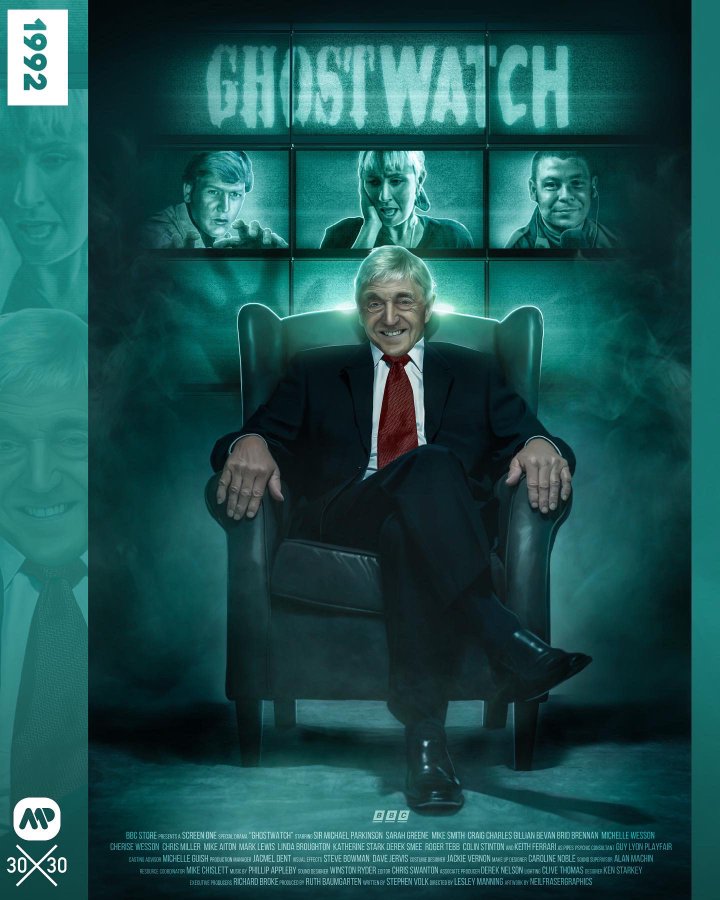

For someone who counts himself a sceptic and unbeliever, Stephen Volk has always had an unhealthy interest in ghosts. He’s probably best known for being the evil mastermind behind Ghostwatch, the BBC drama which pretended to be a “live” broadcast from a haunted house, starring Michael Parkinson and Sarah Greene. Some cages were rattled at the time – questions were even raised in Parliament - and, 30 years later, the programme is oft remembered by fans as one of the standout moments of pant-wetting TV. He also wrote Gothic, the Ken Russell film on the origin of Frankenstein that starred Natasha Richardson as Mary Shelley and Gabriel Byrne as Lord Byron. Amongst many other scripts and books (including the recent Under a Raven’s Wing), he has created and written the multi-award winning ITV drama series Afterlife, starring Lesley Sharp as psychic medium Alison Mundy and Andrew Lincoln as the psychologist studying her, as well as the stage play The Chapel of Unrest which was performed by Jim Broadbent and Reece Shearsmith at The Bush Theatre in London. As if that weren’t enough, his fourth collection of short stories (after Dark Corners, Monsters in the Heart, The Parts We Play and Lies of Tenderness) will be published later this year – and this time it’ll be exclusively ghost stories. What was the first ghost story you read? I can’t tell you the first one I ever read, but I can tell you the first one I ever saw. It was called The Live Ghost and, of all things, it was a Laurel and Hardy short. Yes, I hear you say, but that was supposed to be funny, not scary! I’d honestly beg to differ. Because on my first viewing, aged about four or five, it scared me to death. True, when the drunk falls into the vat of white paint and staggers out, with Stan thinking he’s a spectre, it is meant to be hilarious. But for some reason – I don’t know if it was the grainy black and white – the image gave me the creeps. I’m adamant, to this day, that you can’t tell what is going to terrify young kids, and if you bar them from seeing what is deemed “scary” they will find something scary in the innocuous. I know I did. And in some ways I’ve been on that path ever since. Do you have a favourite ghost story, be it on the page or on the screen? The ghost story that is top on my list, and one that I return to time and again, has to be The Innocents, Jack Clayton’s immaculate adaptation of The Turn of the Screw. I love that he got Truman Capote, a gay writer from the South, to work on the script, bringing a whole new dimension of implied perversion to William Archibald’s stage version. The cinematography is luminous, the chilly moments unforgettable: The tortoise. Miss Jessel across the lake. Quint’s face in the window pane. The illicit kiss of Miles. James’s novella itself is multi-layered and erotically subtle, but somehow in its conversion to the cinema improves upon what is on the page. The house, with its church-like architecture, fighting against the encroaching forces of nature, as the governess’s faith is beleaguered against the pagan and earthy intrusion of the dead. Just genius. What was the first ghost story you wrote? I’ll tell you a secret. The very first thing I ever wrote on my new typewriter when I was fifteen years old was a ghost story. In fact, it was a series of ghost stories! My mates and I were obsessed with those marvellous ITC adventure series that were on TV at the time – The Champions, Randall and Hopkirk, Strange Report, The Prisoner. We all wanted to make our own. Mine was called Ghosthunter and had two characters called Heller and Cavendish (who were basically Peter Wyngarde and Joel Fabiani from Department S), in swinging 1970s London, investigating ghosts. I wrote the ten-page “series format”, drew the standing set, visualised the costumes, and wrote six episodes. Mind you, each one was five pages long, single spaced. Still, when you think about it, it has echoed down the ages and sowed the seeds for many scripts I’ve written since – the sceptic and psychic in Afterlife, the female ghosthunter played by Rebecca Hall in my screenplay The Awakening (StudioCanal / BBCFilms, 2011). What do you think is the enduring appeal of the form? For me the appeal of the ghost story is that the ghost can stand for many things – grief, unfinished business, injustice – and any sort of unresolved flaw in the central character. For me the ghost is often a wonderful projection of what is wrong with them, which is why they have to sort it out – as well as a massive disruption of the status quo of everyday reality, so those two things go hand in hand. I always say if someone proved the existence of ghosts tomorrow, or proved they didn’t exist, it wouldn’t matter to me, I’d go on writing ghost stories, because the ghost as a symbol, as a potent metaphor, remains, and I am interested in what people believe in. And I’ve learnt that most of my characters are on some kind of spiritual journey, which is a hell of a thing for an atheist to admit, but it’s true. Is there anything you’re particularly looking forward to at the Festival itself? What I love about festivals is the sharing. The cross-pollination of ideas you get, from other guests, and from the audience. The notion you have been to four or five talks and certain ideas overlap or others contradict. I love listening to writers discussing craft, always, it’s just the best and most inspiring thing, and the buzz of that never gets old. You never get so sure of how to do this shit that you don’t need to listen. I may be doing an interview on the Friday and I may be doing a talk about my TV work, but really, I’m all ears. UK Ghost Story Festival 202312/12/2022 The Museum of Making at Derby Silk Mill, Derby, DE1 3AF

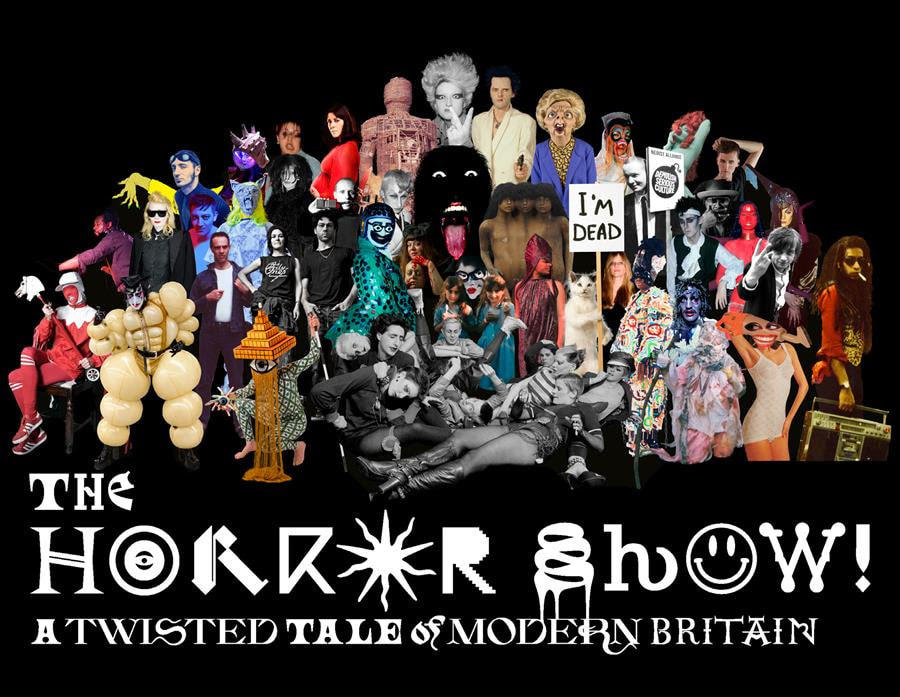

Sat 18th February 2023 Dialogue with the Dead: The Writing of ITV's Afterlife / Stephen Volk Saturday 18th Feb, 3:30pm-4:30pm (Tickets £7.50) Stephen Volk's talk will give you a peek behind the scenes of the much-loved supernatural TV drama starring Lesley Sharp and Andrew Lincoln. Starting with pitch and concept, he will take you through the long journey to production, lifting the lid the collaborative process, and revealing his passionate belief in the importance of "unreality TV". Part of the UK Ghost Story Festival - https://www.ukghoststoryfestival.co.uk/ There will also be a Stephen Volk In Conversation Interview/Q+A at 2:00pm-3:00pm on Friday 17th February and lots of other author events (see above link for full details). This autumn (*opening 27 October 2022*) Somerset House presents a major exhibition celebrating our greatest cultural provocateurs and visionaries, examining how ideas rooted in horror have informed the last 50 years of creative rebellion in Britain.

The Horror Show! is a landmark exhibition that invites visitors to journey to the underbelly of Britain’s cultural psyche and look beyond horror as a genre, instead taking it as a reaction to our most troubling times. Featuring over 200 artworks and culturally significant artefacts from some of our country’s most provocative artists, the exhibition presents an alternative perspective on the last five decades of modern British history in three acts – Monster, Ghost and Witch. Recast as a story of cultural shapeshifting, each section interprets a specific era through the lens of a classic horror archetype with thematically linked contemporaneous and new works. The exhibition offers a heady ride through the disruption of 1970s punk to the revolutionary potential of modern witchcraft, showing how the anarchic alchemy of horror – its subversion, transgression and the supernatural – can help make sense of the world around us. Horror not only allows us to express our deepest fears; it gives a powerful voice to the marginalised and society’s outliers, providing us with tools to overcome our anxieties and imagine a radically different future. The Horror Show! is co-curated by Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard and Claire Catterall, who also conceived the idea. Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard are BAFTA nominated filmmakers and resident artists at Somerset House Studios. Claire Catterall is Somerset House’s Senior Curator. MONSTER Opening The Horror Show! Monster begins by delving into the economic and political turbulence of the 1970s and the high octane spectacle and social division of the 1980s. Against a backdrop of unrest and uprising, it charts the origin story and ascent of the individuals who will go on to disrupt, define and destroy British culture, while exploring the monsters which plague society today. Contributing artists include Marc Almond, Bauhaus, Judy Blame, Leigh Bowery, Philip Castle, Chila Burman, Helen Chadwick, Monster Chetwynd, Jake & Dinos Chapman, Tim Etchells, Noel Fielding, Martin Green & Mark Moore, Pam Hogg, Dick Jewell, Harminder Judge, Daniel Landin, Jeannette Lee, Andrew Liles, Linder, London Leatherman, Don Letts, Luciana Martinez de la Rosa, Lindsey Mendick, Peter Mitchell, Dennis Morris, Matilda Moors, Tim Noble & Sue Webster, Keith Piper, Guy Peellaert, Gareth Pugh, Jamie Reid, Derek Ridgers, Nick Ryan, Steven Stapleton, Ralph Steadman, Ray Stevenson, Poly Styrene, Francis Upritchard and Jenkin van Zyl. GHOST The show’s second act, Ghost, marks the collapse of hyperinflated 1980’s culture into an uncanny temperature change that presided over the 1990s and early 2000s. It traces an unsettling path through to the global financial crisis of 2008, a turning point in time between a century of old and new, at the dawn of a digital age of faceless audiences and invisible cyber wars. Newly commissioned, immersive sound installations from Laura Grace Ford and Nick Ryan highlight the strange frequencies of an age that saw the emergence of trance music and readily accessible sampling machines. Ford’s installation explores the sonic textures of the city to uncover those hiding in the black spots that neoliberalism has failed to assimilate, while Ryan’s voices form a call-and-response, as visitors become spectator, spectacle and a ghost in the machine. Contributing artists include A Guy Called Gerald, Barry Adamson, Hamad Butt, Adam Chodzko, Kevin Cummins, Graham Dolphin, Tim Etchells, Angus Fairhurst, Paul Finnegan, Ghostwatch, Laura Grace Ford, Lucy Gunning, Paul Heartfield, Susan Hiller, Matthew Holness & Richard Ayoade, Stewart Home, Derek Jarman, Michael Landy, Richard Littler (Scarfolk), Jeremy Millar, Haroon Mirza, Drew Mulholland, Pat Naldi & Wendy Kirkup, Cornelia Parker, Steve Pemberton, Nic Roeg, Richard Russell, Nick Ryan, Scanner (Robin Rimbaud), Adam Scovell, Sensory Leakage, David Shrigley, Iain Sinclair, Kerry Stewart, Tricky, Gavin Turk, Richard Wells, Rachel Whiteread, Words & Pictures. WITCH The exhibition’s final act, Witch, focuses on 2008’s financial crash until the present day, and celebrates the emergence of a younger generation and their hyper-connected community – a global coven readily embracing a dynamic grounded in integration and equality. Penny Slinger and Zadie Xa forgo the patriarchal occult and old world druidism with a new sorcery, rooted in ecology and bodily autonomy. Among the works on display are newly commissioned works from Somerset House Studios artists Tyreis Holder and Col Self , as well as a new commission from Linda Stupart and Carl Gent. The act’s final scene features a striking presentation from Turner Prize winning-artist Tai Shani, seen for the first time in the UK, accompanied by an audio installation created by Gazelle Twin and specially commissioned for The Horror Show! Contributing artists include Ackroyd & Harvey, Josh Appignanesi, Ruth Bayer, Anne Bean, Anna Bunting-Branch, Juno Calypso, Leonora Carrington, Coil, Charlotte Colbert, Marisa Carnesky, Cyclobe, Damselfrau, Jesse Darling, Eccentronic Research Council, Jake Elwes, Tim Etchells, Gazelle Twin, Bert Gilbert, Rose Glass, Miles Glyn, Tyreis Holder, Matthew Holness, Sophy Hollington, Bones Tan Jones, Isaac Julien, Tina Keane, Serena Korda, Linder, Hollie Miller & Kate Street, Grace Ndiritu, Col Self, Tai Shani, Oliver Sim, Penny Slinger, Matthew Stone, Linda Stupert & Carl Gent, Suzanne Treister, Cathy Ward, Ben Wheatley, Zoe Williams and Zadie Xa. The distinct signature design of the exhibition is courtesy of architects Sam Jacob Studio and Grammy-winning creative studio Barnbrook. The exhibition will have an accompanying programme of talks and events, with full details announced soon. The special exhibition shop, edited by Faye Dowling’s alternative art store GothShop.co, will feature an exclusive range of limited edition items, including a collectible exhibition book priced at £15, alongside a selection of original and inspired gifts, from clothing and accessories, to limited edition prints, books and zines. You can purchase a book along with your exhibition ticket and save 10%, or choose a book, ticket and poster combo to save 20%. The exhibition catalogue contains original texts by John Doran, Nathalie Olah and Patricia MacCormack, introductions from co-curators Claire Catterall, Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard plus a foreword from Somerset House Artistic Director, Jonathan Reekie. The catalogue is edited by Faye Dowling and designed by Barnbrook. Content guidance: This exhibition contains some graphic and disturbing artworks and therefore may not be suitable for children under 12. Parental guidance advised. On Halloween night, 1992, 11 million viewers tuned into the BBC to watch what they believed to be a live broadcast from a haunted house in Northolt, London. The rest, as they say, is history. Audiences were terrified, switchboards were inundated with complaints, and the BBC disowned the show. But underneath the mania and controversy lies a fascinating and often deeply disturbing exploration of how trauma and abuse can haunt both the mind and the body. Ghostwatch superfans Celluloid Screams and immersive cinema pioneers Live Cinema UK present a special "one night only" 30th anniversary live cinema experience, resurrecting the original spirit of the broadcast for a hauntingly-good immersive celebration of the paranormal, Parky and Pipes. Followed by a Q&A with director Lesley Manning and writer Stephen Volk, peek behind the curtains, and re-enter the glory hole… Content warning: This is a live immersive event. Please be prepared for loud and sudden sounds, lighting, smoke, and jump scares throughout. Produced by Live Cinema UK and Celluloid Screams - Sheffield Horror Film Festival. Screening as part of In Dreams Are Monsters: A Season of Horror Films, a UK-wide film season supported by the National Lottery and BFI Film Audience Network. indreamsaremonsters.co.uk GHOSTWATCH 2022 SCREENINGS

Note: Only Sheffield and London are "immersive" screenings SHEFFIELD: Fri 21 October 2022 - SOLD OUT Sat 22 October 2022 at 7.00pm Extra screening due to phenomenal demand (also followed by Q&A with Lesley Manning and Stephen Volk) Note: This special event takes place at Peddler Warehouse, 92 Burton Rd, Neepsend, Sheffield S3 8BX on Saturday 22 October. All other Celluloid Screams festival screenings take place at Showroom Cinema. Buy tickets here NEWCASTLE: Sat 22 October 2022 Special 30th Anniversary screening at the Star and Shadow 7.30pm (followed by Q&A session with acadmics from Northumbria university) Buy tickets here LONDON: Fri 28 October 2022 at NFT1, BFI South Bank 8.20pm (followed by Q&A with Stephen Volk and director Lesley Manning) The bfi-org page says: "Television’s most infamous hoax remains as terrifying, and challenging, 30 years on." Buy tickets here BRADFORD: Sat 29 October 2022 at the Science and Media Museum 7.00pm (presented by director Lesley Manning, followed by Post-film panel discussion with horror experts Adam Z Robinson (writer, The Book of Darkness & Light, Shivers, Upon the Stair and host of The Ghost Story Book Club podcast), Mike Muncer (host and creator of the Evolution of Horror podcast), Bronte Schiltz (Gothic studies researcher) and Becky Darke (writer, co-host of the Don’t Point That Horror at Me podcast, and regular contributor to The Evolution of Horror and The Final Girls). "On the 30th anniversary of its airing, join us for an in-depth explorative screening of a highly controversial and seriously scary television phenomenon." Buy tickets here CARDIFF: Sun 30 October 2022 at Chapter Arts Centre 3.00pm (followed by Q&A with Stephen Volk) Followed by a screening of Nigel Kneale's seminal BBC TV ghost story The Stone Tape at 5.30pm (introduced by Stephen Volk) In 1992 and on Halloween the BBC gives over a whole evening to an 'investigation into the supernatural'. Four respected presenters and a camera crew attempt to discover the truth behind 'The most haunted house in Britain', expecting a light-hearted scare or two and probably the uncovering of a hoax. They think they are in control of the situation. They think they are safe. The viewers settle down and decide to watch 'for a laugh'. Ninety minutes later the BBC, and the country, was changed, and the consequences are still felt today. With over a million complaints and a generation of children terrified of what might live in their plumbing, this is a rare chance to see that broadcast again and hear from the writer from Pontypridd who changed how we view television. Buy tickets here Check out the article about Ghostwatch by Stu Neville in the current issue of Fortean Times (#424) A feature by Paul Davis on Stephen Volk and Ghostwatch appears in the new issue Fangoria magazine Also upcoming: BBC Radio 3 "Free Thinking" will run a live discussion on Ghostwatch on October 27th 2022 at 10pm, featuring director Lesley Manning and writer Stephen Volk. Presented by Matthew Sweet. George Bass is writing a piece on Ghostwatch for New Scientist online. Stephen Volk has been interviewed about Ghostwatch and his other supernatural writing for an upcoming edition of the "Knock Once for Yes" podcast. Adam Robinson will be interviewing Lesley Manning and Stephen Volk for the Ghost Story Book Club podcast Keep tuned to the Ghostwatch page for more news! 10 Quick Tips About Writing Horror1/10/2022 This article first appeared on the Bang2Write website in 2019, before my new website design. Here it is again, for the record, and for Halloween 2022. Enjoy!

1) Get Your Brain Out of the Way Thinking doesn’t create monsters. Your unconscious does. Don’t think about recent movie hits. Don’t think of old movie legends. In fact, don’t think of anything. Cultivate a dream-time, a coffee-scape. Think of the worst that can happen. Don’t self-censor before you even dream. Go there and return with ideas. And trust them. 2) It’s All About Point of View As I say in my book Coffinmaker’s Blues it’s not about the creature, ghost or alien … It’s about who is seeing it, and why? That’s the key to their inner life and why the hell we should care. POV in the story . . . In a sequence . . . Or in a scene. 3) Junk the Jump Scares The stab of music, the shock reaction, the zombie make-up in the mirror – fuck that shit! It’s dead easy – and dead boring! It gives no depth to your story and doesn’t even make it more frightening a lot of the time. Think of what is going to give your audience nightmares for the rest of their lives, not just spill their popcorn. 4) If You Can’t Explain It – GOOD! The worst thing for horror is a producer who’s a Logic Nazi. No legendary horror ever got where it is from being bombarded by logic notes. Stand up for what you know makes you shiver and shit your pants. If the producer disagrees, or points to the latest James Wan hit, you’ve got the wrong producer. 5) Push It Till It Squeals Like A Piggie David Bowie said the best creative work is done when you’re juuuuuust out of your depth. On tippy-toes in the swimming pool, scared of going under. Always aim for this, especially in horror. It’s on the very edge or risking failure that the magic happens, not by playing safe. MORE: What Is the Difference Between Horror And Thriller? 6) Make it Real Any idiot can write a ghost train ride about a possessed armchair or a demon in a cellar, lit in blue light and licked to death in the grading. And every idiot is.The more plausible and naturalistic you can make your situation and characters, the more your script will stand out from the crud. 7) Ditch the CAPITALS!!!! Take the throttle off your writing – calm down and stop SHOUTING at me! No CAPS. No screamers!!! Write horror prose that creep up and taps my shoulder, and even kisses the back of my neck. 8) Seen it, Done it . . . NEXT! Ditto special effects. You know . . . The crawling across the ceiling, the scabby-face demon make up first seen in The Evil Dead– yawnsville!! If you want to be the best of the best in this genre ditch anything you’ve seen before in another movie. Tough, I know. But you’ll be surprised what you come up with if you mine and trawl your own personal terrors. It’s the one thing that’s utterly unique to you – use it! 9) Don’t Play With Your Food If you’re not a born horror writer, and don’t love the genre with every fibre of your being, don’t worry. But fuck off. How dare you screw around trying to write this shit, because we’ll find you out in a heartbeat!! If your passion is romantic comedy, write romantic comedy. Don’t rain on our parade because . . . what? You think it’s fashionable? You think it’s lucrative, right now? And easy? There’s the fucking door. Don’t slam it on your way out. 10) Remember: You Are Horror It’s there in your own life, your own experiences and those of the people you know. If you don’t see it, and can’t find it, you’re not a horror writer. Alfred Hitchcock was once asked what scared him. He said “Everything.” I don’t know a horror writer that wouldn’t answer the same way. Join our clan. We’ll welcome you with open arms. Like clowns in a dark, dark forest . . . As it turns 100, this utterly chilling silent film deserves more celebration – given it set the template for The Blair Witch Project and many more horrors besides, writes Adam Scovell.

"In the lineage of horror cinema, 1922 surely counts as one of its most important years. It was the year when FW Murnau made his unofficial Dracula adaptation Nosferatu, providing an early scare for audiences even as he fell afoul to copyright breaches. However, around the same time as Murnau's film, another seminal, but today less celebrated, horror was released: the Swedish-produced Häxan: Witchcraft Through the Ages by Danish director Benjamin Christensen. Whereas Murnau defined narrative horror through powerful German Expressionist visuals, the Danish director of this Svensk Filmindustri production innovated with horror's form, creating one of the strangest films of the period – whose eerie atmosphere, stark visuals and experimentation still stand up today." Read the rest of this terrific article on www.bbc.com/culture - Adam send me a few questions on the subject of fake documentary making (I wonder why?), and a few quotes from yours truly are happily included. Stephen VolkScreenwriter and author Archives

December 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed